Introduction to Zoster

Zoster, commonly known as shingles, is a viral infection characterized by a painful rash. It is caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), which is the same virus that causes chickenpox. After an individual recovers from chickenpox, the virus remains dormant in the nerve tissues and can reactivate later in life, leading to zoster. This condition primarily affects adults, particularly those over the age of 50, although it can occur in younger individuals, especially if they have weakened immune systems.

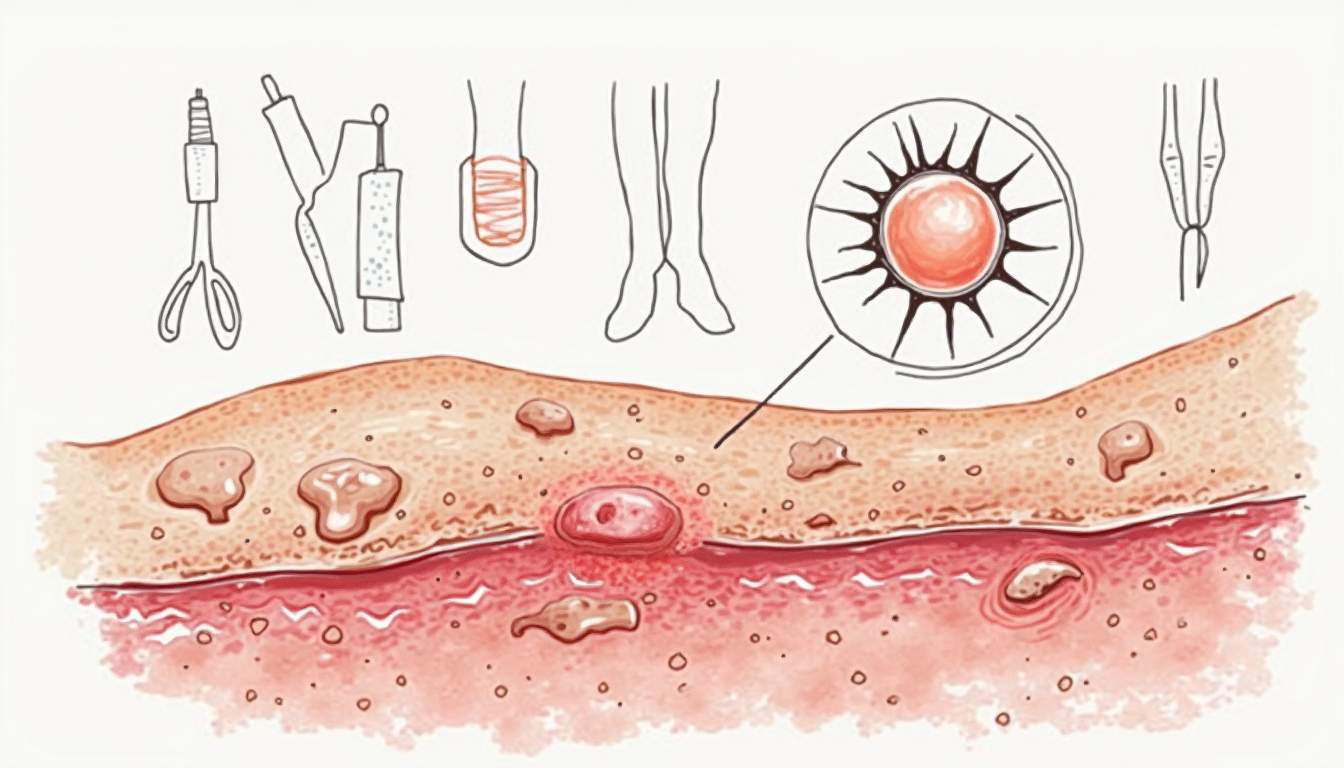

The rash typically appears as a band or strip of blisters on one side of the body, often accompanied by intense pain, itching, and discomfort. Understanding zoster is crucial for dermatologists and healthcare providers, as early diagnosis and treatment can significantly alleviate symptoms and reduce the risk of complications.

This glossary entry aims to provide a comprehensive overview of zoster, including its etiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment options, and potential complications. By delving into these aspects, we hope to enhance the reader's understanding of this dermatological condition and its implications for patient care.

Etiology of Zoster

Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV)

The varicella-zoster virus is a member of the herpesvirus family and is responsible for both chickenpox and shingles. After an initial infection with VZV, typically during childhood, the virus becomes latent in the dorsal root ganglia. Various factors can trigger its reactivation, leading to zoster. These factors include stress, immunosuppression, and aging, which can compromise the immune system's ability to keep the virus in check.

Research indicates that the incidence of zoster increases with age, particularly in individuals over 50 years old. This increase is attributed to the natural decline in cell-mediated immunity as people age. Additionally, certain medical conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, cancer, and autoimmune diseases, can further predispose individuals to zoster due to their impact on the immune system.

Understanding the etiology of zoster is essential for developing effective prevention strategies, including vaccination and public health initiatives aimed at reducing the incidence of chickenpox and, consequently, shingles.

Risk Factors for Zoster

Several risk factors have been identified that increase the likelihood of developing zoster. These include:

- Age: Individuals over the age of 50 are at a significantly higher risk.

- Immunocompromised State: Conditions such as HIV, cancer, and the use of immunosuppressive medications can increase susceptibility.

- Stress: Psychological stress has been linked to the reactivation of the virus.

- History of Chickenpox: Anyone who has had chickenpox is at risk, as the virus remains dormant in the body.

Awareness of these risk factors can aid healthcare professionals in identifying at-risk populations and implementing preventive measures, such as vaccination programs.

Clinical Manifestations of Zoster

Symptoms and Signs

The clinical presentation of zoster typically begins with prodromal symptoms, which may include fever, headache, fatigue, and localized pain or tingling in the area where the rash will develop. This pre-rash phase can last from a few days to a week. Following this, the characteristic rash appears, usually confined to one dermatome, which is an area of skin supplied by a single spinal nerve root.

The rash progresses through several stages, starting as red macules that evolve into vesicles filled with clear fluid. These vesicles eventually crust over and heal within two to four weeks. The distribution of the rash is often unilateral, meaning it affects only one side of the body, and it typically follows a dermatomal pattern, which is a key distinguishing feature of zoster.

In addition to the rash, patients often experience significant pain, known as postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), which can persist long after the rash has resolved. This pain can be debilitating and may significantly impact the quality of life for affected individuals.

Complications of Zoster

While many individuals recover from zoster without complications, some may experience serious issues. The most common complication is postherpetic neuralgia, which occurs in a significant percentage of older adults. This condition is characterized by persistent pain in the area where the rash occurred, often described as burning or stabbing. PHN can last for months or even years, leading to chronic discomfort and reduced quality of life.

Other potential complications include:

- Secondary Bacterial Infection: The open blisters can become infected with bacteria, leading to further complications.

- Vision Problems: If the rash involves the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve, it can lead to herpes zoster ophthalmicus, which may cause serious eye complications, including vision loss.

- Pneumonia: In immunocompromised individuals, zoster can lead to pneumonia, particularly if the virus spreads to the lungs.

Understanding these complications is vital for healthcare providers to monitor and manage patients effectively, ensuring timely intervention when necessary.

Diagnosis of Zoster

Clinical Diagnosis

The diagnosis of zoster is primarily clinical, based on the characteristic appearance of the rash and the associated symptoms. Healthcare providers typically assess the patient's medical history, including any previous episodes of chickenpox or immunocompromised status, and perform a physical examination to evaluate the rash's distribution and characteristics.

In many cases, the presence of a unilateral vesicular rash in a dermatomal pattern is sufficient for diagnosis. However, in atypical cases or in immunocompromised patients, laboratory confirmation may be necessary.

Laboratory Testing

When laboratory confirmation is required, several tests can be utilized:

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): This is the most sensitive and specific test for detecting VZV DNA in skin lesions or cerebrospinal fluid.

- Direct Fluorescent Antibody (DFA) Test: This test can identify VZV in skin lesions but is less commonly used than PCR.

- Serology: Blood tests can detect VZV-specific IgM and IgG antibodies, indicating recent or past infection, respectively.

Accurate diagnosis is crucial for initiating appropriate treatment and preventing complications, particularly in high-risk populations.

Treatment Options for Zoster

Antiviral Medications

The primary treatment for zoster involves antiviral medications, which can help reduce the severity and duration of the illness if initiated within 72 hours of rash onset. Commonly prescribed antivirals include acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir. These medications work by inhibiting viral replication, thereby alleviating symptoms and reducing the risk of complications, such as postherpetic neuralgia.

For patients with severe zoster or those who are immunocompromised, intravenous antiviral therapy may be necessary. The choice of antiviral and the route of administration depend on the patient's clinical status and the severity of the infection.

Pain Management

Effective pain management is a critical component of zoster treatment, particularly for patients experiencing significant discomfort. Analgesics, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids, may be prescribed to manage acute pain. Additionally, adjuvant therapies, such as gabapentin or pregabalin, can be beneficial for neuropathic pain associated with postherpetic neuralgia.

Topical treatments, such as lidocaine patches or capsaicin cream, may also provide symptomatic relief for localized pain. In some cases, corticosteroids may be considered to reduce inflammation and pain, although their use remains controversial and should be carefully evaluated based on individual patient circumstances.

Prevention of Zoster

Vaccination

Vaccination is the most effective strategy for preventing zoster and its complications. The zoster vaccine, known as Zostavax, was the first vaccine approved for the prevention of shingles. It is a live attenuated vaccine recommended for adults aged 50 and older, regardless of whether they have had chickenpox or shingles in the past.

More recently, a recombinant zoster vaccine, Shingrix, has been developed and is now the preferred option due to its higher efficacy and longer-lasting protection. Shingrix is recommended for adults aged 50 and older and for immunocompromised individuals aged 18 and older. The vaccine is administered in two doses, with the second dose given two to six months after the first.

Public Health Initiatives

Public health initiatives aimed at increasing awareness of zoster and promoting vaccination are essential for reducing the incidence of this condition. Educational campaigns can help inform the public about the importance of vaccination, particularly among at-risk populations. Healthcare providers play a crucial role in recommending vaccination to eligible patients and addressing any concerns or misconceptions they may have.

By implementing comprehensive vaccination programs and promoting awareness, public health authorities can significantly reduce the burden of zoster and improve overall community health.

Conclusion

Zoster is a significant dermatological condition with potential complications that can impact patients' quality of life. Understanding the etiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment options, and prevention strategies is essential for healthcare providers to manage this condition effectively. Through early intervention and appropriate care, the risks associated with zoster can be minimized, leading to better outcomes for affected individuals.

As research continues to evolve, ongoing education and awareness will be vital in combating zoster and ensuring that patients receive the best possible care. By fostering a comprehensive understanding of this condition, we can enhance patient outcomes and contribute to the overall advancement of dermatological health.

Visit Our Offices

Services:

- • Medical Dermatology

- • Surgical Dermatology

- • Laser Treatments

- • Cosmetic Dermatology

Services:

- • Medical Dermatology

- • Surgical Dermatology

- • Laser Treatments

- • Cosmetic Dermatology

Visit Our Offices

Services:

- • Medical Dermatology

- • Surgical Dermatology

- • Laser Treatments

- • Cosmetic Dermatology

Services:

- • Medical Dermatology

- • Surgical Dermatology

- • Laser Treatments

- • Cosmetic Dermatology