Definition of Actinic Keratosis

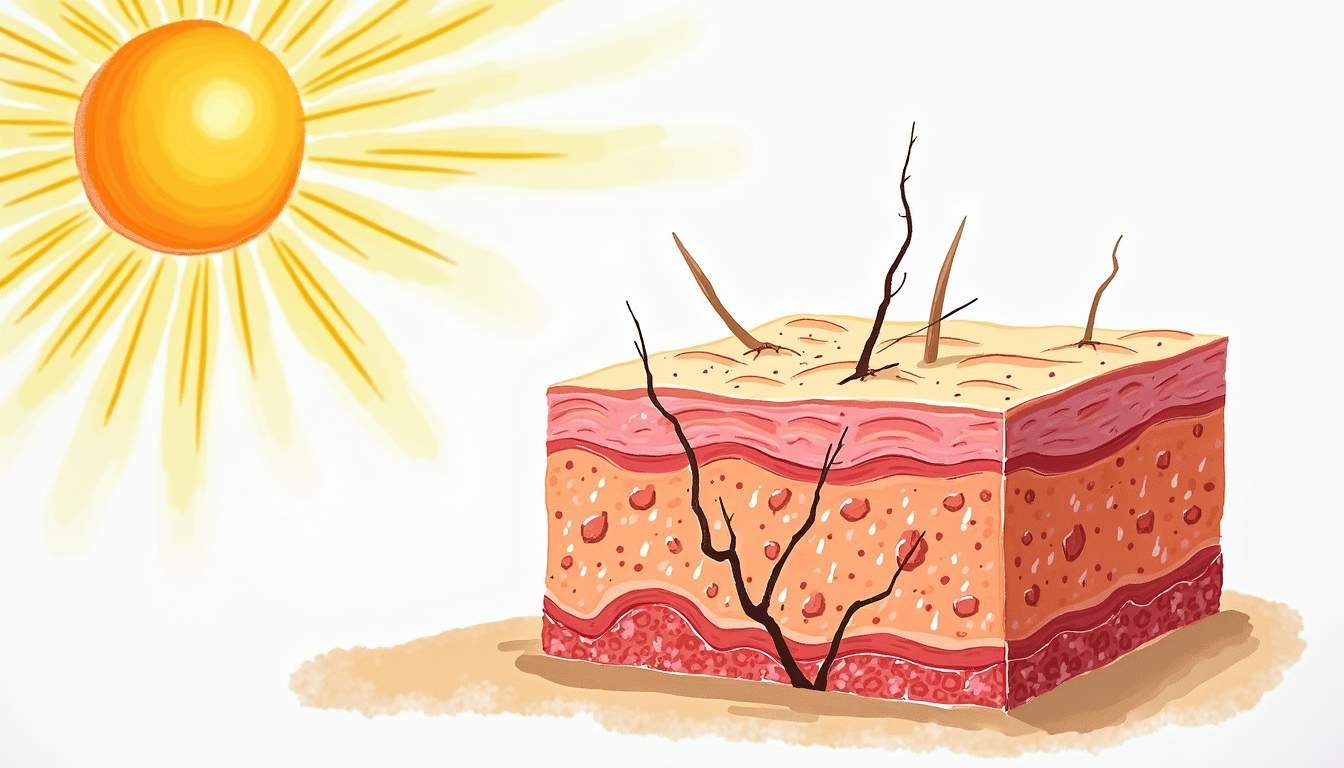

Actinic keratosis (AK), also known as solar keratosis, is a precancerous skin condition characterized by the development of rough, scaly patches on sun-exposed areas of the skin. These lesions arise due to prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, primarily from the sun, leading to changes in the skin's cellular structure. Actinic keratosis is most commonly found on the face, ears, scalp, neck, and backs of the hands, where the skin is most susceptible to sun damage.

While actinic keratosis itself is not cancerous, it is considered a significant risk factor for the development of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), a type of skin cancer. The lesions can vary in color from pink to red, and they may be flat or slightly raised. The texture can range from dry and scaly to rough and crusty, often causing discomfort or itchiness for those affected.

Understanding actinic keratosis is crucial for early detection and treatment, as timely intervention can prevent the progression to skin cancer. Dermatologists emphasize the importance of regular skin examinations, especially for individuals with a history of extensive sun exposure or those with fair skin, as they are at a higher risk for developing this condition.

Causes of Actinic Keratosis

Ultraviolet Radiation

The primary cause of actinic keratosis is prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun. UV radiation damages the DNA in skin cells, leading to mutations that can result in abnormal growth. The cumulative effect of sun exposure over the years significantly increases the risk of developing actinic keratosis. This is why individuals who spend a lot of time outdoors, such as construction workers, farmers, and athletes, are particularly susceptible.

Additionally, artificial sources of UV radiation, such as tanning beds, can also contribute to the development of actinic keratosis. The use of tanning beds has been linked to an increased risk of skin cancer, and dermatologists strongly advise against their use.

Skin Type and Genetics

Individuals with fair skin, light hair, and light-colored eyes are at a higher risk for developing actinic keratosis. This is due to the lower levels of melanin in their skin, which provides less natural protection against UV radiation. Genetics also play a role; a family history of skin cancer or actinic keratosis can increase an individual's risk. Furthermore, older adults are more likely to develop this condition as the skin's ability to repair itself diminishes with age.

Symptoms of Actinic Keratosis

Physical Characteristics

Actinic keratosis lesions typically present as small, rough, scaly patches on the skin. They may appear as flat or slightly raised spots and can range in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. The color of these lesions can vary, including shades of pink, red, or brown. Some may have a crusty or dry appearance, while others might feel itchy or tender to the touch.

In some cases, actinic keratosis can develop into larger lesions that may bleed or become ulcerated. It is essential for individuals to monitor any changes in their skin and seek medical advice if they notice new growths or changes in existing lesions.

Associated Sensations

Many individuals with actinic keratosis report sensations such as itching, burning, or tenderness in the affected areas. These sensations can be particularly bothersome and may lead to scratching, which can exacerbate the condition or lead to secondary infections. It is crucial for those experiencing these symptoms to consult a dermatologist for evaluation and potential treatment options.

Diagnosis of Actinic Keratosis

Clinical Examination

The diagnosis of actinic keratosis typically begins with a thorough clinical examination by a dermatologist. During this examination, the dermatologist will assess the skin for characteristic lesions and may inquire about the patient's medical history, including sun exposure and any previous skin conditions. The visual examination is often sufficient for diagnosis, but in some cases, a biopsy may be performed to rule out other skin conditions or to confirm the diagnosis.

Dermatologists may utilize tools such as dermatoscopes, which provide magnified views of the skin, to better evaluate the lesions. This technology can help differentiate actinic keratosis from other skin conditions, such as seborrheic keratosis or basal cell carcinoma.

Biopsy and Histopathological Analysis

If there is uncertainty regarding the diagnosis, a skin biopsy may be performed. This involves removing a small sample of the affected skin for histopathological analysis. The sample is examined under a microscope to assess the cellular changes associated with actinic keratosis. The presence of atypical keratinocytes, which are indicative of actinic keratosis, can confirm the diagnosis and help determine the appropriate treatment plan.

Treatment Options for Actinic Keratosis

Topical Treatments

Topical treatments are often the first line of defense against actinic keratosis. These treatments typically involve the application of medications directly to the lesions. Common topical agents include 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), imiquimod, and diclofenac. These medications work by targeting the abnormal cells in the lesions, promoting their destruction and allowing healthy skin to regenerate.

5-fluorouracil is a chemotherapy agent that disrupts the growth of abnormal skin cells, while imiquimod is an immune response modifier that stimulates the body's immune system to attack the abnormal cells. Diclofenac, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), is used to reduce inflammation and promote healing. Patients may need to apply these treatments for several weeks to achieve optimal results.

Procedural Treatments

For more extensive or resistant actinic keratosis lesions, procedural treatments may be recommended. These include cryotherapy, which involves freezing the lesions with liquid nitrogen, causing the abnormal cells to die and slough off. Curettage and electrosurgery is another option, where the lesion is scraped away and the area is cauterized to prevent bleeding.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a newer treatment option that involves applying a photosensitizing agent to the lesions and then exposing them to a specific wavelength of light. This process activates the agent, leading to the destruction of the abnormal cells. Each of these procedures has its advantages and potential side effects, and the choice of treatment will depend on the individual patient's condition and preferences.

Prevention of Actinic Keratosis

Sun Protection Measures

Preventing actinic keratosis primarily revolves around protecting the skin from UV radiation. Individuals are encouraged to adopt sun safety measures, including wearing broad-spectrum sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher, even on cloudy days. Sunscreen should be applied generously and reapplied every two hours, especially after swimming or sweating.

Wearing protective clothing, such as long sleeves, wide-brimmed hats, and sunglasses, can further shield the skin from harmful UV rays. Seeking shade during peak sun hours, typically between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m., is also advisable. These preventive strategies are essential for individuals at higher risk, including those with fair skin, a history of sunburns, or a family history of skin cancer.

Regular Skin Examinations

Regular skin examinations by a dermatologist are crucial for early detection of actinic keratosis and other skin conditions. Individuals should perform self-examinations monthly, looking for any new or changing lesions. Dermatologists recommend annual skin checks for those at higher risk, as early intervention can prevent the progression of actinic keratosis to skin cancer.

Conclusion

Actinic keratosis is a significant dermatological condition that warrants attention due to its potential to progress to skin cancer. Understanding its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options is essential for effective management. By adopting preventive measures and seeking regular dermatological care, individuals can significantly reduce their risk of developing actinic keratosis and its complications. Awareness and education are key components in combating this prevalent skin condition, ensuring that individuals can maintain healthy skin and minimize their risk of skin cancer.

Visit Our Offices

Services:

- • Medical Dermatology

- • Surgical Dermatology

- • Laser Treatments

- • Cosmetic Dermatology

Services:

- • Medical Dermatology

- • Surgical Dermatology

- • Laser Treatments

- • Cosmetic Dermatology

Visit Our Offices

Services:

- • Medical Dermatology

- • Surgical Dermatology

- • Laser Treatments

- • Cosmetic Dermatology

Services:

- • Medical Dermatology

- • Surgical Dermatology

- • Laser Treatments

- • Cosmetic Dermatology